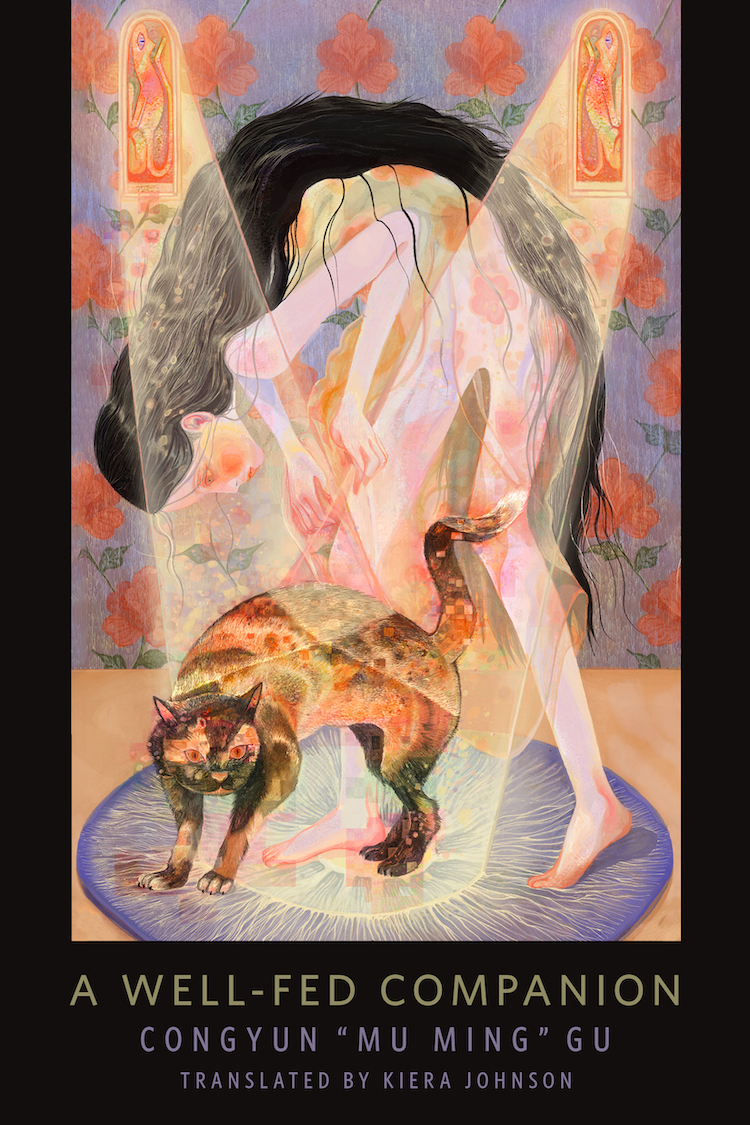

In a future where human souls take the form of animal companions, Hairuo struggles to keep her cat fed on the tedium of her day-to-day, until she meets an enigmatic stranger who has a well-fed cat…and an appetite of his own.

as if awakened, she turns her face to yours;

and with a shock, you see yourself, tiny,

inside the golden amber of her eyeballs

suspended, like a prehistoric fly.

—Rilke, “Black Cat”[1]

Hairuo was the only person in the neighbourhood who had a cat.

Every morning, she woke to the roar of the hair dryer. Hairuo’s roommate liked her hair fluffy to match her toy poodle, so she had to wash and style it every day. Hairuo preferred to spend an extra thirty minutes in bed, doing nothing but staring up at the ceiling, imagining its rough, uneven lines as mountain ranges. The hair dryer droned on—she pictured herself on the wings of an airplane about to take off, overlooking the world turned upside down. Shadows of trees outside the window moved across the ceiling like giant birds soaring over the landscape. Could someone’s soul fly like that?

She let her hand hang off the side of the bed to stroke her cat. Her companion, her little soul.

The cat lay underneath the bed, only the white tip of his tail peeking out as it swept impatiently from side to side. She knew he didn’t like the noise. They were always at their most distant from each other in the mornings, kept apart by the incessant drone of the hair dryer, the increasingly dazzling sunlight, and irrepressible feelings of hunger and anxiety. He hid in the dark and folded up his slender mouse-like tail.

Hairuo got up, dressed slowly, and plucked a strand of black cat hair from her white sleeve. It felt thick and stiff, and she hesitated for a moment before throwing it away. The cat had a small frame, but he had been losing a lot of fur recently and appeared all the more fragile for it. He wasn’t eating well. Cats were picky eaters, she knew that, but that didn’t mean she could just let him starve. Nor could she rightly feed him nothing but bland, tasteless food, even though she herself only ate the bento box lunches from the convenience store downstairs: neat, uniform meatballs rolled on an assembly line and small cubes of diced carrot, day after day.

Hairuo’s roommate stuck her head out from the bathroom, her hair bound up in rollers. Her poodle lay on his back, his tongue lolling happily from his mouth, his tiny eyes concealed by curly fur. As Hairuo’s roommate began to loosen the rollers, she eyed Hairuo’s dishevelled hair and pallid face through the mirror with an impatient expression.

“You know, having a cat isn’t an excuse not to make an effort—”

“Goodbye,” said Hairuo. She thought she heard the cat snarl quietly from the darkness below her bed.

Few people were still on the street by the time Hairuo headed out the door. A man with a bulging backpack, towing a short-legged, long-bodied sausage dog, passed her as he staggered towards the bus stop. She recognised him as another resident of their building. He’d once pressed a sweat-soaked sports game ticket into her hand, making her palm grow so sticky that she’d hardly been able to disguise her laugh. Afterwards, she’d seen him talking with her roommate by the neighbourhood’s raised flowerbeds, sausage dog and poodle sniffing one another from head to tail; their cautious politeness had seemed on the verge of blossoming into warmth at any moment. Hairuo had left in a hurry.

Her cat didn’t go to work with her like other people’s dogs did; he stayed home alone instead. Even though “home” was a crowded shared apartment, it was the only place that was dark, quiet, free enough to suit him. He needed plenty of rest, far more than Hairuo herself. While he napped in his cat bed at home, she stared at the files and drafts on her computer screen and felt her mind drifting far away. Only the sound of her manager’s footsteps walking back and forth could jolt her awake again. The manager’s boxer dog always followed behind him, her thick shoulder blades rolling beneath her sleek fur as she went. Every time the two of them went past, Hairuo felt glad that her cat didn’t have to come face-to-face with a dog like that.

She forced her attention back to her work, putting the cat out of mind for the time being, and resumed tapping away at her virtual keyboard. Dogs lay peacefully beneath desks around the office; there was complete silence apart from the quiet rustle of their fur being stroked. Hairuo’s seat was the only one with nothing beneath it.

In the winter of the year 1900, eighteen-year-old Emmy Noether and her rare snow leopard were admitted into the University of Erlangen—

In the winter of the year 1900, eighteen-year-old Emmy Noether and her rare snow leopard didn’t sit in the front row in class. She was never sure whether she or her snow leopard were the greater curiosity for her male classmates. But she was already no stranger to standing out from the crowd—

In the winter of the year 1900, eighteen-year-old Emmy Noether listened to lectures by Hilbert, Klein, Minkowski, and other master mathematicians in Göttingen, but she was at her freest when she let her rare snow leopard roam through Bavaria’s Black Forest. Ravens and albatrosses circled high up in the sky above, and Emmy watched as they became black spots in the distance. From their perspective, the rivers, fields, and villages were as minute and abstract as a chessboard. As day after day passed in careful study for Emmy, her snow leopard gradually shed his spots to become a dazzling white. The purest alpine snowfield on Earth—the snow leopard’s native state.

Hairuo paused the tapping of her fingertips on the screen and gazed out of the bus window, picturing the snow leopard in her mind’s eye. It was a rainy evening, and the drizzle painted rivulets of indigo and pitch black down the window like a hasty watercolour. She saw her own face half-illuminated in the wash, her lips dark and eyeliner smudged as if by the rain. She reached out a hand to draw a pattern in the condensation on the window, then turned her head, gently pressed the Enter key, and ended the paragraph. The story had begun as a nerve impulse in her brain, but typed out it transformed into pulsing computer bytes that flowed into the external hard drive installed behind her ear. The hard drive was designed to look like a delicate hair clip, the tip of which was implanted deep into her skull, leaving only the old-fashioned amber outer shell exposed beneath her hair.

In her imagination, the snow leopard was Emmy Noether’s soul, its agility and beauty visible for everyone to see. But exceptional beauty was often more frightening, more abhorrent, than ordinary ugliness; only a bird flying high enough would pay it no mind. Companions could grow, the colour of their fur could change, Hairuo thought, but a snow leopard was a snow leopard, and a cat could not become a dog.

Emmy Noether fed her snow leopard the purest of thoughts, and so his black spots disappeared completely. Hairuo kept trying to come up with a good ending for her story. She thought of her little cat—what was there for him to eat from her ordinary life? What could he grow to become?

Hairuo’s gaze drifted, then focused once again. The inside of the bus was dimly lit; the man and dog sitting beside her both looked drowsy, and the man almost bumped into Hairuo’s shoulder as the bus rocked and swayed, while his husky companion rested her head on her owner’s polished leather shoes. The dog was beautiful, just like her owner, but Hairuo would never be a dog person.

She jumped off the bus, opened her umbrella, and splashed her way through a vast puddle. The cat that often roamed around the street corners was nowhere to be seen today. Her heart stuttered for a moment, echoing the rain falling to the ground, and she hoped that it was just hiding from the weather somewhere.

Hairuo had once tried to imagine what that cat’s owner might look like. The cat was white with a circle of black fur on the top of its head like a woollen hat—it should’ve looked amusing, but Hairuo had never managed more than a half smile at the sight of it. The cat was thin enough for its ribs to show. She had no way to feed it, so she’d taken photos and put them online, hoping its owner would see them and show up, but nothing had come of it. Not many people had cats.

Hairuo was well aware that people who had lost their companions might already be long gone. Dogs could barely survive on their own for any length of time. Cats were used to spending time alone, wandering around, hiding, almost completely independent from anyone or any community, but they were still companions in the end.

Hairuo waited in the pitter-patter of the rain until twilight gradually thickened into night and the splashing puddles grew still. She returned home beneath flickering streetlights. Vague sounds of laughter could be heard from her roommate’s bedroom, but Hairuo couldn’t tell whether the laughter was real or canned, coming from her roommate’s favourite show. Hairuo had watched it before too: the host had a Saint Bernard companion that weighed a hundred kilogrammes. Every sentence the host said produced massive reactions from the audience, and everyone repeated his jokes endlessly the following day. When the show first started airing, his Saint Bernard had been a tiny puppy, but over time she transformed into that honey-and-milk-coloured mountain of a dog in the broadcasting studio today.

Dogs got their energy from joining packs, chasing and sharing the spoils of their catch. But cats were not the same.

Hairuo walked into her room and kept the lights off as she felt about in the dark. Her fingertips hit the touch point on the hard drive. Faint light glowed beneath her hair, then followed the lines of her cheeks to shine on her arms as it flowed down and away. Fifteen hours of visual data, sixteen hours of auditory data, twenty-four hours of consciousness and subconsciousness—the amount of information flowing out seemed immense, but there was little real nourishment to be found beneath the redundant noise of clichés and empty phrases.

The cat squeezed silently into his half-moon bed. In the flickering rays of light, Hairuo couldn’t see how well he was eating; she just hoped that he might grow a little bigger. He should enjoy the story about Emmy Noether, but she wasn’t sure how he would take the disappearance of the stray cat from the street corner.

Cats’ stomachs were far more sensitive than dogs’.

The fluorescent light faded. The cat slipped soundlessly out of his bed and gazed back at her; in the darkness, his eyes shone like stars. She reached out a hand and he began to lick her palm, his tiny tongue rough, damp, warm. This didn’t happen often. With a jolt, she realised she had been longing for it.

Hairuo would always remember the day the cat came. Her whole class lined up in the corridor, waiting their turn for their companions to take shape. Hairuo was the last person in line. The sky was a strange, reddish-orange colour, like the surface of Mars, and she watched the white poplar trees on the sports field shiver in the dusty air. It was April. She didn’t join in with her classmates’ enthusiastic whispered discussions. Lots of them wanted Great Danes or English mastiffs—they grew quickly so long as they had enough to eat—while others wanted poodles or Chihuahuas, which were energetic despite their small size, and not picky eaters to boot.

The first mental imaging scan took twenty-one minutes. Memory networks formed flesh and blood, modes of perception synthesised into skin and fur, thought patterns built the crisp white skeleton, while the fire of life—the beating heart—came from your most deeply held desires, hidden on the lowest level of the neural network. These tiny animals were a part of people, but they were lifelong companions too; they swallowed everything you saw, heard, and thought, and grew into forms that flesh-and-blood human bodies had no way to contain.

Why couldn’t companions be trees? That way she wouldn’t have to feed it. But when Hairuo saw that ingenious skeleton gradually take shape, sharp nails retreating into paws and a tiny tortoiseshell kitten appearing before her eyes, she never wished for a tree again.

Hi, little monster. She reached out to stroke his mottled yellow-black tail.

The cat retreated and swiped; his thin claws left three shallow lines down her arm. It took three weeks for this welcome gift to fade away.

Cats can be easy to look after, but they come with their challenges too, Hairuo’s class teacher told her, begrudging the effort; he’d never liked her much. There were always a few students in each year group who had cats, but hers was just so small . . .

She couldn’t remember what else the teacher had said to her, but she’d skipped class the next day and stayed in her dormitory instead, lost in thought. The cat lay on his stomach on the windowsill and watched the packs of dogs out on the sports field. They were playing Frisbee. Occasionally she raised her head and the cat’s ears would twitch slightly, but he never turned to look back at her.

All of a sudden, he hiccoughed repeatedly, one after another, then spat out a ball of sticky yellow bile. Hairuo was terrified at first; she didn’t learn until later that it wasn’t unusual for a cat to throw up like this sometimes. She went straight out the following day to have that amber-coloured hard drive embedded in her skull, where it recorded electrical signals directly at the neuronic level. This type of implanted processor could store massive amounts of information with high spatiotemporal resolution. Hairuo was determined to experience more of the world, put herself out there too, so that she could feed the cat well.

Ten years passed by. She never cut her hair short again; she didn’t want anyone to see the hard drive’s outer shell. But the cat still grew slowly, and her little soul became even more estranged and indifferent than she had believed possible. She’d always thought that he had no hopes of his own and so no disappointments either, that he just wandered like a shadow through his own world—up until that day when she felt the rough warmth of his tongue on her hand.

Companions hadn’t always been animals.

When Hairuo’s parents’ generation had been children, people’s souls appeared as strikingly realistic digital portraits, projected onto screens. The portraits had high resolution surveillance cameras for eyes, circular microphone arrays for ears, and pseudo-stereo speakers for mouths. The most important thing was the heart—the kernel in which deep learning frameworks were processed. It gathered together every carefully composed or hastily scrawled line of writing from its owner, every sentence of speech, and combined these with the ocean of information that could be found online to undergo an individualised modelling process. When soul portraits left the factory, they were little more than blank slates; it was only after interacting with their owners that they began to learn and grow, gradually revealing their innate form.

And so for the first time, a person’s soul—that ancient secret which had long been sealed up in people’s skulls or chests—found a new place to live. By the time Hairuo’s parents’ generation grew up and entered adulthood, more often than not they had to submit their soul portraits’ web address along with their resumes.

But problems followed. The careful deductions of the algorithm often produced portraits that defied expectations. An arrogant person might manifest a timid, self-doubting soul, while a despondent soul might belong to a seemingly optimistic person. A person’s hidden depths, which they themselves had had no way of seeing clearly before, were gradually brought to light with every word they spoke. There was nowhere to hide from the omniscient, grasping hand of the algorithm.

Lots of people demanded this nakedness be covered up again. They said that just as our ancient ancestors used furs to protect their bodies, so too should soul portraits be protected, hidden. But there were even more people who disagreed, saying that in its explorations of the outside world, humanity had already gone too far for too long; our estrangement from the spiritual world grew deeper and deeper every day, bringing with it endless misunderstandings and disputes, all blood and tears and pain. People needed a vehicle, a channel, an interface through which they could externalise the soul, that part of themselves that was both innate since birth and in constant flux.

The final plan was both an escalation and a compromise: the virtual image on a screen shifted into something real and warm. 3D-printed alloy skeletons, lifelike flesh and fur bioengineered with stem cell differentiation technology, as well as a refined positronic brain—together they formed a small animal companion, a dog or a cat. A companion was easier to swallow than a mirror. The real selves that people didn’t want to see, didn’t dare confront directly, were hidden in flesh, concealed by skin and fur. Cautiously extending an animal’s nose, tongue, teeth, or paws towards the world felt more acceptable somehow.

Hairuo’s generation was already well used to these furry souls. Companions were independent and warm, far superior to the ice-cold mechanical nakedness of soul portraits exposed on screens. How many sweethearts fell in love at first sight because their dogs touched noses and sniffed each other’s tails in curiosity at dog parks? Apparently it was easier, less hassle, than online dating. During job interviews, managers’ dogs would sniff out the most dependable and obedient candidates to join the workforce. Performance records improved, and managers always said it was a more reliable method than endless rounds of interviews. But more important than all that, even more people found that there was simply no way to reject their true self anymore: alternately alert and resourceful, powerful and mighty, elegant and adorable; a self that you could snuggle up to and hold tight in your arms when you felt hopeless or frustrated, whose soft fur you could bury your face in; a self that would always stand by you. Cases of clinical depression and even suicide rates fell sharply after companions came onto the scene. After all, how could anyone truly not like this little self of theirs?

Stories abounded about dog companions saving humanity. There were far fewer stories about cats. Not many people had cats.

Hairuo’s workplace was half the city away. She could never think of the right metaphor to best describe the building, with its glass curtain walls and lights that never went out. From the vantage point of the offices high up inside, she could look down on the neat skeleton outline of the paths in the park below. Small patches of grass were set between the paths, following the standard configuration for every business district, neighbourhood, and street—dog parks. The green spaces were particularly busy after lunch, when dogs chased each other across the grass while their people chatted beside the paths. Hairuo had never been down there before. She couldn’t understand all the fuss over a ball being thrown. She chewed slowly at her desk, used her chopsticks to quietly pick out the dog treat that came free with her bento box, and threw it away.

Hairuo’s daily tasks involved dragging a few lines, buttons, and boxes around her screen, arranging them in certain forms, and then annotating the distance in pixels between the lines and buttons. A one-pixel difference might make her eyelids twitch, but a discrepancy of three pixels was enough to prompt her manager to come over and knock sharply on her desk. In her early days at this job, Hairuo had wanted to argue with him, but she’d given up at the first sight of that boxer dog panting hotly and trailing strings of saliva. She could only ever nod and give the manager a faint, distant smile to show she understood.

Dogs developed relationships by sniffing or chasing each other, but Hairuo had a cat. Cats breathed lightly, walked quietly; they hid instinctually from coarse, panting things. Distance was her armour, polite smiles her mask. She knew she was the problem here, so she tried not to complain too much.

Hairuo had studied digital art and design at university, and found this job right after graduation. Sometimes she wondered whether it was really the right fit for her, but she quickly realised there was no sense in thinking like that. One of her university classmates had had a cat too, and after graduating he’d moved into a two-storey studio that lacked all of the personal space and distance which best suited cats. Despite this, when Hairuo had visited once, she’d seen his cream-coloured Ragdoll cat asleep and perfectly happy on a soft cushion in the corner of the room. Behind his cat was a three-dimensional virtual art space, built between two workstations and three projectors, within which rays of light changed colour endlessly to form images of rivers, waterfalls, forests, and gardens that responded to and resonated with the viewer’s presence. Hairuo’s classmate said that hesitation, exploration, and discovery were the inspirations for his work; that in the modern age, it didn’t matter whether you were talking about modes of creative expression or humanity’s aesthetic experiences—neither could be limited any longer to two-dimensional surfaces. The Ragdoll cat had woken up then and strolled gracefully through the lights and shadows, the fur on her large frame soft and fluffy, and her blue eyes had gazed tenderly at Hairuo.

Hairuo thought of her own little tortoiseshell cat at home.

She had realised early on that for an ordinary person such as herself, coming from an ordinary family and working at an ordinary job, a cat was a debt that could never be repaid, a soul hungry for something she didn’t have to give. There was nothing from her daily commute, nor from the minute distances between pixels, that she could use to feed him. Compared with that plump Ragdoll cat, Hairuo’s cat was too small, too thin. She never knew when he might disappear on her. She had to fill herself up with as much as possible, so that she could try to feed him well.

But her life was suspended between her shared apartment and her job, so insubstantial that one gust of wind could blow it all away. And so around her ten-hour working day, she carved out time to wade through ancient texts, navigating the weft and weave of unfamiliar words during her lunch break and commute. The complex visual appearance of contemporary art made the written word appear simple and one-dimensional by comparison, long since outdated. The only advantages of written texts lay in their portability and low cost.

However, while readily available information was more than enough to excite dogs, her cat was far more sensitive, more selective. The most popular writing could make him vomit incessantly; long-forgotten things were more to his taste. Hairuo had no choice but to constantly unearth old stories, and probe deep into her own mind as well. Many nights, her dreams would needle her awake with a painful start, trembling, to type out line after line of a story in a daze, fingers uncertain, the hard drive’s lights flashing beneath her hair, and in the darkness he would watch her silently.

In 1925, after the lighthouse keeper Clarence Salter died, his wife, Fannie Salter—

In 1925, following the death of the lighthouse keeper Clarence Salter and after many hard-won fights, Fannie Salter was finally allowed to continue watching over her husband’s lighthouse on her own. It was one of forty-five lighthouses in Virginia. Fannie had grown up in a fishing village by the sea, so she was no stranger to the winding coastline or the white tower standing tall on the cliff’s edge.

A pilot whale kept her company in the waters nearby, and when the weather was good, sailors could catch a glimpse of its dorsal fin amongst the waves. On nights thick with fog, Fannie first climbed the stone steps up to the lighthouse, and then the iron steps leading straight to the control room, where she lit the oil lamps. From her little lighthouse keeper’s cabin, Fannie had a direct view of the light on the tower’s top floor; she woke every two hours to look out the window and make sure that the lamps had not stopped burning. In even worse weather, she would ring a fog bell every fifteen seconds for a whole hour straight, until all the steamboats had passed safely through the channel. People said that the tolling of the bell sounded like a whale’s mournful moan.

Pilot whales preferred to live in groups, but Fannie worked alone at the lighthouse for twenty-two years. No one knew how she passed the long years in the face of that boundless, unchanging ocean, nor how she fed her lonely pilot whale. After her death, people discovered everything she had written in the lighthouse keeper’s cabin, describing everything from her first meeting with Clarence Salter in the greenness of youth right up to his departure from this world. Once one-hundred-watt light bulbs replaced the work of lighthouse keepers, no companion ever took the shape of a pilot whale again.

Fannie Salter raised a whale in a lighthouse. Hairuo paused her typing and lay back on the bed; the lines on the ceiling above her became the waves of the North Atlantic ocean.

Twenty-five years’ worth of memories, digested across another twenty-five years. Hairuo imagined the whale waiting quietly in the gloomy ocean depths, countless tiny food particles floating around him like shoals of fish. What kind of life could be rich enough to keep him well-fed? Fannie hadn’t read many books, nor had she ever gone far from the sea coast where she’d grown up, but she’d still found a way to feed her whale.

Hairuo stroked the cat’s ears. He lay nestled by her side, curled up in a ball and looking even smaller than usual. Her stories of distant places combined fact and fiction in equal measure: she had never heard of anyone who had a whale or a snow leopard for a companion. She created stories of her own invention and fed the cat with them, but he still grew so slowly.

She knew why. Her life was so dry, so atrophied—her imagination tried to paint masterpieces but managed only simple sketches. But with the cat by her side, she could feel the warmth of his body and the gradual strengthening of his heartbeats as they drummed in his chest. He didn’t often come so close to her.

She tossed and turned in the dark as if a rough tongue lapped at her heart. Little by little she slipped into a dream and saw a boundless, open sky above surging ocean waves. The urge was undeniable. She jumped. The ocean was warm, like flesh and fur—a warmth she hadn’t felt for a long time. When she woke up, the cat was lying in the crook of her arm.

She thought she knew then what he needed.

She noticed him from the very first day he came into the office. A grey linen shirt, slender fingers, bitingly cold eyes, and a mouth whose corners curled into something that was not quite a smile. The afternoon sun was dazzling; one by one, others in the office lowered their window blinds, while he alone closed his eyes, tilted his head back to let the light play across his face, and held that position, motionless, for a long time. Hairuo was no stranger to drifting off like that, and the arch of his back in the rays of sunlight held a familiar curve as well. She found herself imagining how his pupils would look in the light.

And he didn’t have a dog.

After lunch, he and Hairuo were the only people left in the office. She’d wanted to take advantage of the lunch break to have a read through of her drafts, but even as her fingers slid over the tablet screen, her eyes wouldn’t focus. She heard her breath come heavy from the pit of her stomach, completely unlike her usual self.

“You’re not going on a dog walk?” She forced herself to open her mouth, then regretted it an instant later. The obviousness of that fact and her self-consciousness were both clear to see.

“It’s awful.” He frowned. “Don’t you think?”

Hairuo nodded, indescribably pleased. Although companions took animal form, they were still your purest self. Data and patterns of connection, the alloy skeletons printed from them, the positronic brain: they were all so much more real than flesh-and-blood bodies, revealed more of your innate nature. So why didn’t anyone else think it terrible, then, to expose their naked souls to one another, to let them chase and play together? She couldn’t stand it. Cats needed quiet, rest, concealment.

“You like reading?” He lifted his chin slightly. She shut the cover over her tablet on pure instinct. The ochre cover was blank, no text or images on its surface; if it weren’t for the thinness of the tablet, it would look exactly like an old hardback book without its dust jacket. The world inside there was more real to her than anything else in the office—it was what she used to feed her cat.

But she couldn’t help herself; she wanted to let him see. Just a little would be okay.

“I . . . write sometimes, nothing serious.”

He nodded. She waited for what felt like an age.

“I heard that on Leo Tolstoy’s last day alive, he wanted to squeeze an elephant onto a train and run away.” He spoke as if it were an undeniable historical fact. “The eighty-year-old man left home in secret. He even wore a crumpled straw hat to disguise himself, but his elephant companion gave him away. Later, when he lay on his deathbed in the stationmaster’s office, reporters from all over the world came to the train station, bringing their dogs with them, and in amongst the hordes circled around to watch, there stood that elephant. Can you imagine it? An elephant.” He winked at her, creasing the lines at the corners of his eyes.

His stories were long, detailed, ever-unfolding. Tolstoy’s elephant was no more than a ball of string that he tossed towards Hairuo, and she followed that string into a forest labyrinth full of rare birds and beasts, gasping in surprise as she went; she fell further under his spell with each step she took. In his world, her laughter echoed, her tears overflowed. His stories were like suspension bridges strung up in the treetops of some primaeval rainforest, whisking reason and emotion along for the ride as they hovered in complex time and space, sometimes plunging down into the abyss and other times climbing up to mountain peaks. The centrifugal force raging in Hairuo’s mind almost made her want to abandon reading altogether, but her whole being was like some pitiful asteroid, easily caught and engulfed by the star-like gravitational pull of his words.

Unlike the contemporary art installation she’d once wandered through, ancient words were more intimately tied to the human imagination, penetrated deeper into the self. He said that was human nature. He held forth on primitive languages appearing by chance tens of thousands of years ago, Chomsky and Pinker’s universal grammar, how written language had arisen from the coordinated evolution of the human mind. As humanity evolved from one generation to another, those who could manipulate language to suit their needs held the evolutionary high ground; their superiority was assured by their grasp of language. This was true even now, when people were so occupied by contemporary art. The deepest recesses of the soul, he told her, were still captured, transformed, remoulded in the symbols of written language.

A creator’s soul lived in their works. By then, she was already captivated by the souls in his stories, which always took shape as strange animals—the insatiable Wan Qi who survived on a diet of other people’s dreams, or the headstrong, obstinate Taowu. Hairuo saw shadows flickering amongst them, almost familiar somehow, and she wanted to draw closer, pick out his soul from their midst, but it always slipped from her grasp.

If his words were really just crude fragments of his soul, then how could he feed his cat with them alone? What nourishment could be found from them? His life was no less ordinary and repetitive than Hairuo’s; perhaps he was simply more gifted than her.

She couldn’t help herself. She wanted to get closer to him, but he kept his distance. She knew that civil distance well, the rigidity behind polite smiles. She’d been like that once as well, but she didn’t want it this time. She’d already wandered alone for far, far too long. Cats might dread the noisiness of a pack of dogs, but they could still wish for another cat’s company as they paced their solitary way through the long nights.

Hairuo began to swap manuscripts with him. She was anxious, hesitant at first: her stories were so much weaker, flimsier than his. But more important, she was afraid that he might be able to read the vague longings hidden between the lines. He’d once said that cats cannot be fed false things. Every faint tremble, every minute touch, every painful nightmare or moment of reality—these were where a cat’s real nourishment lay.

“You have to have the courage to walk naked in the street, let everyone see you. Only then can you feed a cat properly,” he said, leaning against the window.

“And that’s . . . different from dogs? They’ll eat anything.” She gazed out the window to the grass where dogs ran in happy circles around their people. One dog bowed its golden forelegs tamely towards the ground, its enormous hind legs sticking up into the air, making the people around burst out laughing. Its owner stretched out a hand and the dog immediately began licking it, over and over. Hairuo knew there must be light information chips in the owner’s hand, which could be collected by content merchants, dried out, compressed, cut up, and packaged into a soluble storage medium—neat, clean, and portable. The chips only needed to touch the contact points on the dog’s tongue to be converted into delicious electrical signals, which rapidly adjusted the cell composition and metal skeleton of the dog’s artificial body. The dog would grow bigger and bigger, and its owner wouldn’t even have to work for it.

“That’s why even big dogs are easily tamed, but the same tricks don’t work on cats.” The corner of his mouth lifted slightly, revealing traces of smile lines, “Ironically, dog food makers often have cats themselves.”

“What do you think having a cat for a companion really represents? Aesthetic taste, observation skills, imagination, creativity, or—?” Hairuo couldn’t stop herself from leaning towards him.

“All of that, but also none of that.” He wasn’t evading her question; his sudden turn to face her made her jump, was all. “I’m impressed you can already think about this.”

“So what do you say, then?” For the first time, she mustered up enough courage to look him directly in the eye, hoping to find some kind of answer there, but his pupils were pitch-black and impenetrable. She couldn’t see anything in them.

“Freedom, independence, as well as . . .” He met her gaze, and a sudden smile spread across his face, “How would I know? No one knows. They’re our lifelong companions, the externalisation of our truest selves, and that fact alone demands that we spend forever in exploration, trying to understand them. For the vast majority of the time, we’re solitary creatures, but occasionally there’ll be a moment of companionship.”

Hairuo’s heart thundered in her chest. This tenderness frightened her the most, suddenly breaking through his distant facade as if he could see right through her. She wasn’t sure if she’d ever be able to prepare herself for it.

“I like your stories.” He took her hand and her mind became a blank slate; she didn’t hear a single word he said next.

“. . . remind me of my younger self. Pure and unique . . . delicious.”

“That day—you were just teasing me. You knew that companions didn’t exist in the past.” Hairuo couldn’t hold back a slight smile as she fiddled with the roasted chicken wings on her plate: she was a terrible cook and had wasted several packs of wings before getting these ones just right. “Nerve signal data extraction, signal processing, modelling, shaping: the technology for making animal companions is only around twenty years old.”

“You can’t say that for sure.” He feigned seriousness. “Maybe Ovid’s Metamorphoses isn’t just a simple book of legends; maybe it’s actually an accurate record of the existence of companions. The practice of killing cats during mediaeval witch hunts also clearly points to the fact that human souls can appear in nonhuman forms. Let alone the ones in novels—familiars, guardian spirits, vessels for the soul . . .”

“They all count as companions?” She let out a light laugh. “I didn’t expect you to still read children’s fantasy books.” They’d been officially dating for a month now, and she’d already lost her reserve from when they’d first met.

“They’re the things that really matter,” he said indifferently, peeling meat precisely off the bone with his knife and fork.

Her heart gave a faint shiver; as usual, she understood his meaning without needing words. Those guardian spirits, strange creatures—once constant childhood companions, up until the moment when modern science had disenchanted the ancient, chaotic world four hundred years ago with its ice-cold mechanical touch. As humans interacted with this new world, those spirits—intangible yet all too real—gradually faded to transparency; it was only through the written word that you could catch a fleeting glimpse of their long-forgotten truths. The things that really matter. In her stories, Hairuo used fact as the warp and imagination as the weft, weaving together each and every fragment of them, trying to capture a little of that which had been lost.

“So, why do you think there are only dogs and cats?” she asked softly, hoping he would say how unusual, how precious it was that the pair of them had found each other.

“Probably out of some kind of nostalgia.” He thought for a moment, then lifted his glass and moistened his lips with red wine. “Millions of years ago, humans explored the outside world together with newly domesticated animals. But it’s more complicated now—exploring the outside world, your inner world, moving endlessly from outside to inside and back out again—there’s so many detours to take . . .”

“Oh,” Hairuo sighed, setting her fork down. She took his hand gently, and he stiffened for a moment, then let her. She thought she followed his line of thinking, understood that he cared about far more than just the similarities between the two of them. Just like everyone with a cat companion, Hairuo also cared about those impulses, beliefs, dreams, and experiences that were so personal it was difficult to share them with others. Those faint, profound traces left behind by unknown ancestors in ancient symbols, moulding the self and the recognisable world. The souls that returned to people’s sides in completely new ways.

Yet Hairuo wished that for him, she could be like a dog whose tail wagged whenever she saw him—but when he was immersed in his own world he forgot her entirely.

He was even more cat-like than she was, Hairuo had come to realise. Her cat still hid in his bed, only sticking his head out to look around: a little curious, a little fearful of strangers. She hadn’t written any stories for a long time now, but the cat had grown bigger anyway, his mouse-like tail becoming thicker, rounder, fluffier. Was she afraid?

“I can’t eat any more.” He set down his knife and fork. “Next time, come to my place, and bring your cat.”

What she really wanted to remember was every touch, every breath, every kiss. What she wanted to forget was time itself. But all that was left in the end was a pain like new birth.

His cat was twice the size of hers, an ash grey, long-haired Norwegian forest cat with a swiftly moving gaze just like his own, who gave a low growl at the first sight of Hairuo’s cat, and then howled. Hairuo had no idea what to do; he didn’t say a word. His big cat closed in on her little cat step by step, but just as Hairuo was about to rush in between them, he stopped her.

“Cats have their own ways of getting along.” He glanced meaningfully at her.

She could only bite her lip and try to stifle her anxiety. Her little cat trembled in the shadows, not making a sound—then the large cat brandished a paw, and her little cat suddenly flashed his own claws.

A blood-curdling yowl. A deep scratch split open across the large cat’s face, starting at the corner of her eye and slashing downwards. He cried out, seemingly involuntarily, losing himself, and turned to look at Hairuo with an unfathomable glint in his eye.

“It was an accident—” she explained hurriedly, her mind dark with fear. But then the large cat snarled loudly, seized the little cat’s nape in her mouth and flung him against the sharp corner of the coffee table.

Hairuo screamed and rushed over to pick up her little cat. Her mind was in utter chaos. What frightened her the most—herself or him?

“He won’t die.” He had regained his composure and his indifference. “Cats have more lives than you or I, you know that they can survive anything. But I never expected—you seemed . . .” He paused, as if there were something else he wanted to add, but he stopped there.

She couldn’t speak. Hairuo carried her little cat into the bathroom, his scalp torn and gaping. Although companions were man-made, their skin was still textured like a real animal’s, and she was helpless in her panic at the sight of her cat’s mangled head. She knew he couldn’t die, but she ransacked the bathroom in search of bandages and cotton buds anyway. She tore open the drawers one after another and then, suddenly, stumbled across the terrible sight of tiny scraps of fur, cut into neat two-inch squares: orange, tortoiseshell, and tabby.

“What are you doing? Stop worrying about the cat. Come here.” Impatience leaked into his languid voice. Her hair stood on end, like a cat with its hackles raised. The truth was easy to see, but she had been lost in her ignorance, a dog pointlessly chasing her own tail, when she should have been keeping her distance, scrutinising him, thinking for herself.

“Come here.” His footsteps gradually grew closer. She closed the drawer in a hurry. Her cat was motionless in her embrace, as if tensed to leap away from her at any moment. Her mouth was dry—what was she meant to do now?

She let him pull her back into the room. She felt almost on the verge of collapse, and yet, as bewildered as she was, somehow in spite of everything, a kind of excitement was flooding her mind. He didn’t know that she had discovered the truth. As soon as he found out, she knew he would withdraw, and once withdrawn, he would bide his time to strike. She had a predator’s instincts after all, untamed by anything.

Fingers held back her pulse, breath ghosted over skin. Lost in these subtle sensations, her consciousness peeled away like clothing from her body and fell into her cat. Opening her eyes wide, she saw every speck of light within the gloomy room; with a twitch of her nose she differentiated all of the strange smells permeating the air; not a single subtle sound escaped unnoticed past her swivelling ears. Every inch of her senses stretched out to their fullest, every drop of perception flowed into a powerful current. Boundless, open, a warm ocean embraced her, her body unfurled almost to the point of total oblivion—until her cat nipped lightly at her fingertips.

Her head cleared in an instant. She watched him narrow his eyes slightly, and the shadow of his eyelashes fell on his face in a picture of pure, unaffected innocence. The fabric of her consciousness folded back into her body, and as she dressed she slowly drew closer to whisper in his ear.

“What on earth do you feed her? She’s grown so big.”

“The words of the sages, the tremors of the soul, crystals and flames . . .” he murmured, and for a split second she thought she’d misunderstood him.

He was telling her the truth, but that was also his bait, wasn’t it?

There was something innately euphoric in the act of killing. Underneath the hidden neural networks, the fire of life arose from the oldest and cruellest of desires. He had grasped much earlier than she had the truth that lay beneath cats’ indifferent appearances.

“And what about… other cats?” she asked in a low voice, and, ignoring the sudden freezing of his expression, held her little cat close as she rushed out the door.

Both of their bodies ached dully, but some secret part of her was glad that he’d underestimated her after all.

He’d taught her a lesson.

It wasn’t too late.

She still saw him around the office. The two of them maintained a polite distance, pretended nothing had happened, and it turned out to be not too difficult for them. The thing that changed was that Hairuo began to go for runs around the park during her lunch breaks: that way, she wouldn’t have to be alone with him.

She didn’t share manuscripts with him anymore. She vaguely understood the secret source of his astonishing works now. It was far too dangerous for cats to expose themselves to the outside world: she had almost become his next offering, vanished into his words, his rich themes, narrative forms, subplots, and paragraphs, dissolved into the spaces between flesh and bone in that grim, captivating Norwegian forest cat. Inside her little cat’s positronic brain were soft layers of information—her known and unknown self. Just a few seconds of contact with the touch point would have been enough time to complete the transmission. Her fear lingered for a long time afterwards.

But there were unexpected rewards as well. After those first few nights when her tears had fallen uncontrollably, she finally discovered that her cat had fully doubled in size. Lying on the bed now, he no longer looked mouse-like and frail. She hadn’t expected him to enjoy the taste of pain. And for someone like her, a living shadow held apart from the people around her, the only thing that could cause real pain would be another cat.

Did she miss it? Or regret it? She didn’t know. Two souls could understand each other for a short time, but two hunters could not coexist for long.

That she had escaped at all was lucky enough. Cats were destined to be solitary.

A few injuries were to be expected.

After she handed in her resignation, Hairuo changed all of her contact details and moved to another city, where she lived alone and began to write stories again. She not only wrote in shorthand notebooks now, but also posted her work online. Nor did she write nothing but lonely, lifeless stories anymore; the scope of her work grew ever vaster, unconstrained. She wrote about how Madame de Pompadour’s rose-coloured mare ruled over the stables of Louis XV, wrote about how Simone de Beauvoir’s ring-necked pheasant flaunted his tail feathers when the two of them mixed with the men in the Café de Flore. She kept reading, not just novels and biographies but myths and legends too, philosophy books, theories of evolution and histories of technological development—the mark of him that still remained.

The stories of the snow leopard and the pilot whale lay dormant in Hairuo’s notebooks still. She could never forget how their few immature paragraphs had been absorbed into her little cat’s flesh and blood.

Hairuo also remembered the elephant, and those other strange animals that had once transfixed her. Later, she found out that behind the elephant stood Tolstoy’s first wife, Sonya, who had transcribed his manuscripts for decades despite the couple’s hatred for each other. Biographers blamed Sonya for the great writer leaving home to die; Tolstoy’s will didn’t mention her even once. The author’s wife lived her whole life without leaving behind a soul taking shape for the world to see. People could only guess at the form it would have taken, but Hairuo wasn’t that person anymore.

She cut her hair short, exposing the amber-coloured hard drive behind her ear and the tip where it embedded into her skull; she was no longer afraid.

Max Weber’s disenchantment had been realised when companions took shape; Heidegger’s poetry unfolded in winding bitstreams. At the endings of her stories, she wrote freedom, freedom: ancient legends reappearing in the world of the living, wandering souls finally returned to their bodies. Her thoughts were rich, flowed from her pen to the paper like the wind. The cat lay beside her on the desk, napping with his paws tucked under himself and his back holding that familiar curve. He’d already grown much heavier, his body now as round as a ball; only his face remained sharp still. The wound on his head, fully healed by now, was almost completely invisible.

Her stories gradually began to gain some traction, and she came to know a few other writers as well, many of whom also had cats. But she never met up with them in person.

One day, Hairuo returned home to her apartment to find a crumpled envelope in her mailbox. Her heart constricted in her chest. Had he tracked her down? The envelope was torn in places, revealing glimpses of what looked like photographs inside.

Trembling with fear, Hairuo opened the envelope, only to let out a sigh of relief when she saw an invitation card with a familiar poodle paw print on its front. It was her old roommate. She was now engaged to the man with the sausage-dog companion, writing to invite Hairuo to come back for their wedding. Hairuo smiled slightly; they hadn’t seen each other for a long time now, but people with dog companions were always so warm-hearted.

Before I forget, someone with a cat came looking for you, have a look at the photos, Hairuo read on the little slip of paper attached to the invitation. Her nerves drew tight again. She’d never told anyone about him.

The photograph was of a man she had never seen before, wearing a woollen hat, and although his expression was somewhat blurred, Hairuo could just about make out a shy smile on his face. In his arms he held the white cat that Hairuo thought had long since disappeared into the rainy night.

On the back of the photograph, he’d written the rather long-winded tale of how he’d lost his cat, seen Hairuo’s post online and found her again, how he’d wanted to pay Hairuo a visit but had hesitated, and so on and so forth. Finally, in a roundabout way, he asked for her contact details, and perhaps—she could even read behind his cautious words—he could bring his cat to come and see her cat.

She shook her head, thinking to toss the photograph into a drawer as she went by. But then she paused. Perhaps. Her cat yawned, extended his claws, and revealed his sharp teeth. She would never be able to forget that day, nor his deft, precise attack; she should have known it from the very first time she saw him.

The scars were faint now, invisible, and desire began to stir. This time, she’d changed.

Of course, you’re welcome to come visit, she wrote in her reply. After all, we both have cats.

“A Well-Fed Companion” copyright © 2024 by Congyun “Mu Ming” Gu, translated by Kiera Johnson

Art copyright © 2024 by Inju Park

[1] Translated by Stephen Mitchell. Sourced from https://poets.org/poem/black-cat [accessed 3 November 2021].

Buy the Book

A Well-Fed Companion